There are a lot of KM-related words beginning with the letter C.

Connection, Collection, Collaboration, Curation, Conversation, Communities, Culture…

There’s one which you might not have thought of, but which I think is pretty important.

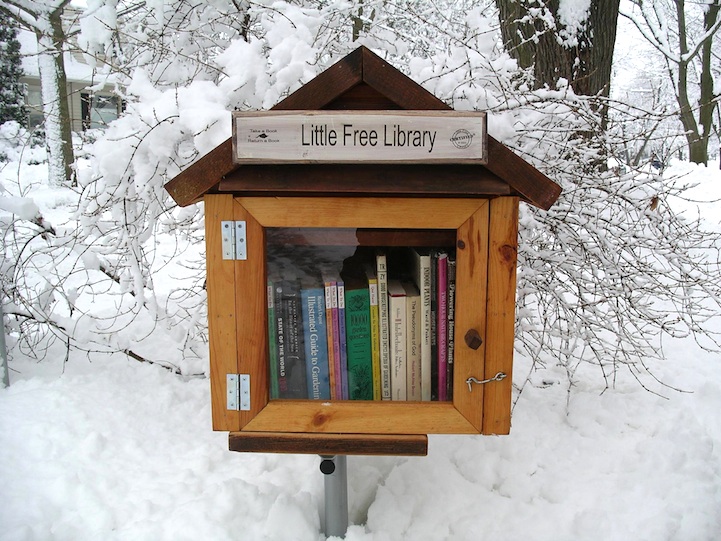

Here’s a clue.

That's right, Coffee. One of knowledge management’s most powerful tools.

Not so sure? Let me share with you a couple of quotes from middle managers in a smart, knowledgeable organization which can spend over £1bn annually on major programmes and projects. I was interviewing a range of staff to help them create an Organisational Learning Strategy, and the C-word kept coming up:

"Coffee conversations happen all the time – our networking keeps us alive. People say we’re a process-driven organization, I just do not agree. We’re relationship-driven."

"Do people regularly go into a Lessons database - ”I’m just about to start a project, I wonder what’s there?”. I can tell you that they absolutely won’t! They might have a coffee conversation, but the learning won’t come from the document – it’ll come from “Blimey, someone told me you did this before, is there anything you can give me tips on?”

We're talking here about a conversation in an area around the coffee machine or in-company Starbucks, rather than coffee taken back to a desk. So why does a conversation over coffee work where formal KM tools and techniques fail?

- It's neutral. It feels like you're not working!

Coffee is a social activity. It's something we would chose to do for enjoyment. Asking to talk something over with a coffee is a sugar-coated request which most people accept without another thought. Especially if they're not buying.

- You get to talk and you get to listen. It's not often you see people balancing coffee on the edge of laptops and communicating with each other through PowerPoint. Far more common is a straightforward conversation, complete with the eye contact which PowerPoint and flipcharts often rob us of...

- It's transparent. Others see you talk. Having a coffee with someone is a pretty visible way to share knowledge. Many of our interactions are semi-private email, telephone or instant message exchanges. Whilst that's not a problem as such, an e-mail-only exchange takes away the serendipitous "Oh, I saw you having a coffee with Jean yesterday, I didn't know you knew her - we used to work together..." connections which might follow.

- It makes you pause, and go slow. "Warning, contents may be hot." You can't drink a coffee quickly. There's a forced slow-down of the exchange and time between sips for the conversation to bounce between the participants. It prevents "drinking from a fire-hydrant syndrome!"

- Others stop and talk whilst you're in the queue. Double serendipity! Not only might you be seen having the conversation, but it's very common for one of both of a pair of knowledge-sharers waiting the coffee line to connect with others whilst they wait. You don't get that in emails!

- It's a culture-spanner. Coffee is the second most used product in the world after oil, and it is the world's second most popular drink, after water. That makes it pretty much a universal currency for buying knowledge-sharing time in any country and any culture.

- It stimulates your brain. Coffee doesn't just keep you awake, it may literally make you smarter as well. Caffeine's primary mechanism in the brain is blocking the effects of an inhibitory neurotransmitter called Adenosine. By doing this, it actually increases neuronal firing in the brain and the release of other neurotransmitters like dopamine and norepinephrine. Many controlled trials have examined the effects of caffeine on the brain, demonstrating that caffeine can improve mood, reaction time, memory, vigilance and general cognitive function.

- It's very cost effective! Set-up costs might extend to some cafe-style tables, but the ongoing operational costs are unlikely to be a problem.

So there we have it. The humble, but very effective cup of coffee.

What other KM tool or technique spans all cultures, balances speaking and listening, slows the world down enough for sharing to soak in, encourages serendipity and openness, makes you smarter and more receptive, costs a pittance and doesn't even feel like working?

Mine's a caramel macchiato...

So Steve Ballmer leaves Microsoft within the next year, and his epitaphs are already being cooked-up by many commentators.

So Steve Ballmer leaves Microsoft within the next year, and his epitaphs are already being cooked-up by many commentators.

Billy Ray is a homeless Kansas man who received an unexpected donation when passer-by Sarah Darling accidentally put her engagement ring into his collecting cup. Despite being offered $4000 for the ring by a jeweller, he kept the ring, and returned it to her when, panic-stricken, she came back the following day. Sarah gave him all the cash she had in her purse as a reward, and as they told their good-luck story to friends - who then told their friends - her finance decided to put up a website to collect donations for Billy Ray. So far, $151,000 have been donated as the story has gone viral around the world. Billy Ray plans to use the money to move to Houston to be near his family. You can see the whole story

Billy Ray is a homeless Kansas man who received an unexpected donation when passer-by Sarah Darling accidentally put her engagement ring into his collecting cup. Despite being offered $4000 for the ring by a jeweller, he kept the ring, and returned it to her when, panic-stricken, she came back the following day. Sarah gave him all the cash she had in her purse as a reward, and as they told their good-luck story to friends - who then told their friends - her finance decided to put up a website to collect donations for Billy Ray. So far, $151,000 have been donated as the story has gone viral around the world. Billy Ray plans to use the money to move to Houston to be near his family. You can see the whole story

Our BMW is nearly 8 years old now. It’s been brilliant, and it’s had to put up with a lot from a growing family, and now a dog with an affinity for mud and water.

Our BMW is nearly 8 years old now. It’s been brilliant, and it’s had to put up with a lot from a growing family, and now a dog with an affinity for mud and water.