Earlier this month I took my family to visit Highclere Castle in Berkshire. It is beautiful Victorian Castle set in 1000 acres of parkland, and is home to the Earl and Countess of Carnarvon. It is best known though, for its role in the TV period drama Downton Abbey which has gripped not just the British viewing audience, but audiences around the world, and particularly in the US. It’s become quite a phenomenon, nominated for four Golden Globes.

As we took the tour of the inside of Highclere Castle, we were expecting to see merchandise and references to the TV series wherever we looked, given the worldwide acclaim for Downton Abbey. “This is the room where Mr Pamuk died…” “This is the spot where Lord Grantham kissed Jane…” We couldn’t have been more wrong! It would be quite possible to tour the entire castle and completely miss its starring role in the TV series! Surely a missed opportunity by the owners, the Earl and Countess of Carnarvon?

What they did have on display in the huge basement was a large Egyptology exhibition which told the story of their great grandfather, Lord Carnarvon who, together with Howard Carter, discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922. That momentous discovery in the Valley of the Kings is the real story of Highclere Castle, and we got the feeling that the current Earl and Countess of Carnarvon were a little indignant that the vast majority of visitors to Highclere Castle are only there because of a piece of engaging TV fiction!

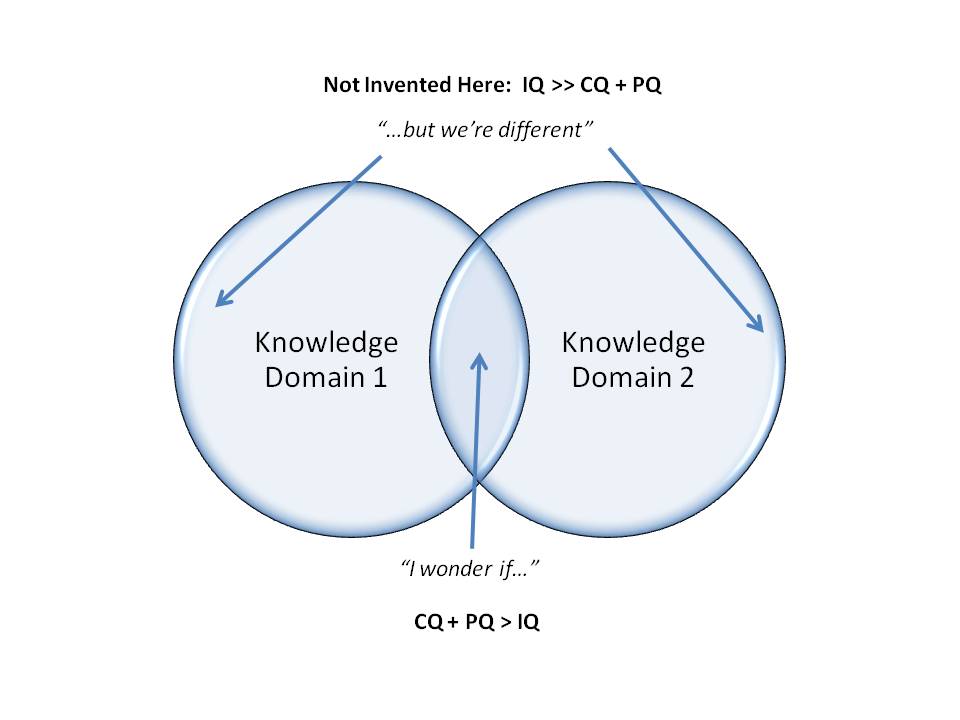

It’s a perfect illustration of the difference between “what you know” and “what you are known for”.

Throughout our organisations, there are hundreds and thousands of people who have real stories to tell from their past knowledge, experiences and roles – yet they are only known for their current job title. How do we enable this past experience and know-how, which often lies as buried as Tutankhamun’s tomb, to be rediscovered?

As knowledge professionals, this should be one of our priorities.

One way is to enable the creation of internal profiles which encourage employees to describe the interests and past experiences as well as their current position – and to embed their use in the habits of the workforce. Many organisations do this very well, notably MAKE award winners BG Group and Schlumberger.

Another approach, often complimentary, is to draw out the experience of others through a collective response to a business issue for example via a “jam” session. I was speaking with Deloitte in the UK last week, and they described the success of their “Yamjam” sessions which often surface knowledge from surprising locations.

The creation of open networks, and the provision of easy mechanisms for staff to join networks of their interest also makes it easy to mobilise knowledge and experience from wherever it lies.

Finally, the use of knowledge cafes, world cafes and other free-flowing conversational processes will set the stage for connections and contributions which might otherwise never surface.

These approaches all enable knowledge and experience from the present (what you are known for) and the past (what you know) to be shared and reused.

Not only would the fictitious butler Carson approve, but also the very real Earl and Countess of Carnarvon.

So Steve Ballmer leaves Microsoft within the next year, and his epitaphs are already being cooked-up by many commentators.

So Steve Ballmer leaves Microsoft within the next year, and his epitaphs are already being cooked-up by many commentators.