There was a helpful thread in the sikm-leaders forum last week when someone asked for ten responses to complete the statement “You know knowledge is being effectively managed when...” I thought it was a really practical way to explore how it feels, and looks – how people behave, when KM is really working. Here are my ten suggestions:

You know knowledge is being effectively managed when...

Leadership. Leaders in the organisation are role models, challenging people to ask for help, seek out, share and apply good practices this inspires curiosity and a commitment to improve. The organisation is learning!

Learning. People instinctively seek to learn before doing. Lessons from successes and failures are drawn out in an effective manner and shared openly with others who are genuinely eager to learn, apply and improve. Lessons lead to actions and improvement.

Networking. People are actively networking, seamlessly using formal communities and informal social networks to get help, share solutions, lessons and good practices. The boundaries between internal and external networks are blurred and all employees understand the benefits and take personal responsibility for managing the risks.

Navigation. There are no unnecessary barriers to information, which is shared by default and restricted only where necessary. Information management tools and protocols are intuitive, simple and well understood by everybody. This results in a navigable, searchable, intelligently tagged and appropriately classified asset for the whole organisation, with secure access for trusted partners.

Collaboration. People have the desire and capability to use work collaboratively, using a variety of technology tools with confidence. Collaboration is a natural act, whether spontaneous or scheduled. People work with an awareness of their colleagues and use on-line tools as instinctively as the telephone to increase their productivity.

Consolidation. People know which knowledge is strategically important, and treat it as an asset. Relevant lessons are drawn from the experience of many, and consolidated into guidelines. These are brought to life with stories and narrative, useful documents and templates and links to individuals with experience and expertise. These living “knowledge assets” are refreshed and updated regularly by a community of practitioners.

Social Media. Everybody understands how to get the best from the available tools and channels. Social media is just part of business as usual; people have stopped making a distinction. Serendipity, authenticity and customer intimacy are increasing. People are no longer tentative and are encouraged to innovate and experiment. The old dogs are learning new tricks! Policies are supportive and constantly evolving, keeping pace with innovation in the industry.

Storytelling. Stories are told, stories are listened to, stories are re-told and experience is shared. People know how to use the influencing power of storytelling. Narrative is valued, captured, analysed and used to identify emergent patterns which inform future strategy.

Environment. The physical workplace reflects a culture of openness and collaboration. Everyone feels part of what’s going on in the office. Informal and formal meetings are easily arranged without space constraints and technology is always on hand to enhance productivity and involve participants who can be there in person.

Embedding. Knowledge management is fully embedded in people management and development, influencing recruitment and selection. Knowledge-sharing behaviours are built-into induction programmes and are evident in corporate values and individual competencies. Knowledge transfer is part of the strategic agenda for HR. The risks of knowledge loss are addressed proactively. Knowledge salvage efforts during hurried exit interviews are a thing of the past!

Now your top ten will probably be different to mine (although you’re very welcome to borrow and adapt them). This kind of approach encourages us to look well beyond the technology which often disproportionately demands our attention.

Taken from the Consulting Collison Column in an upcoming edition of Inside Knowledge

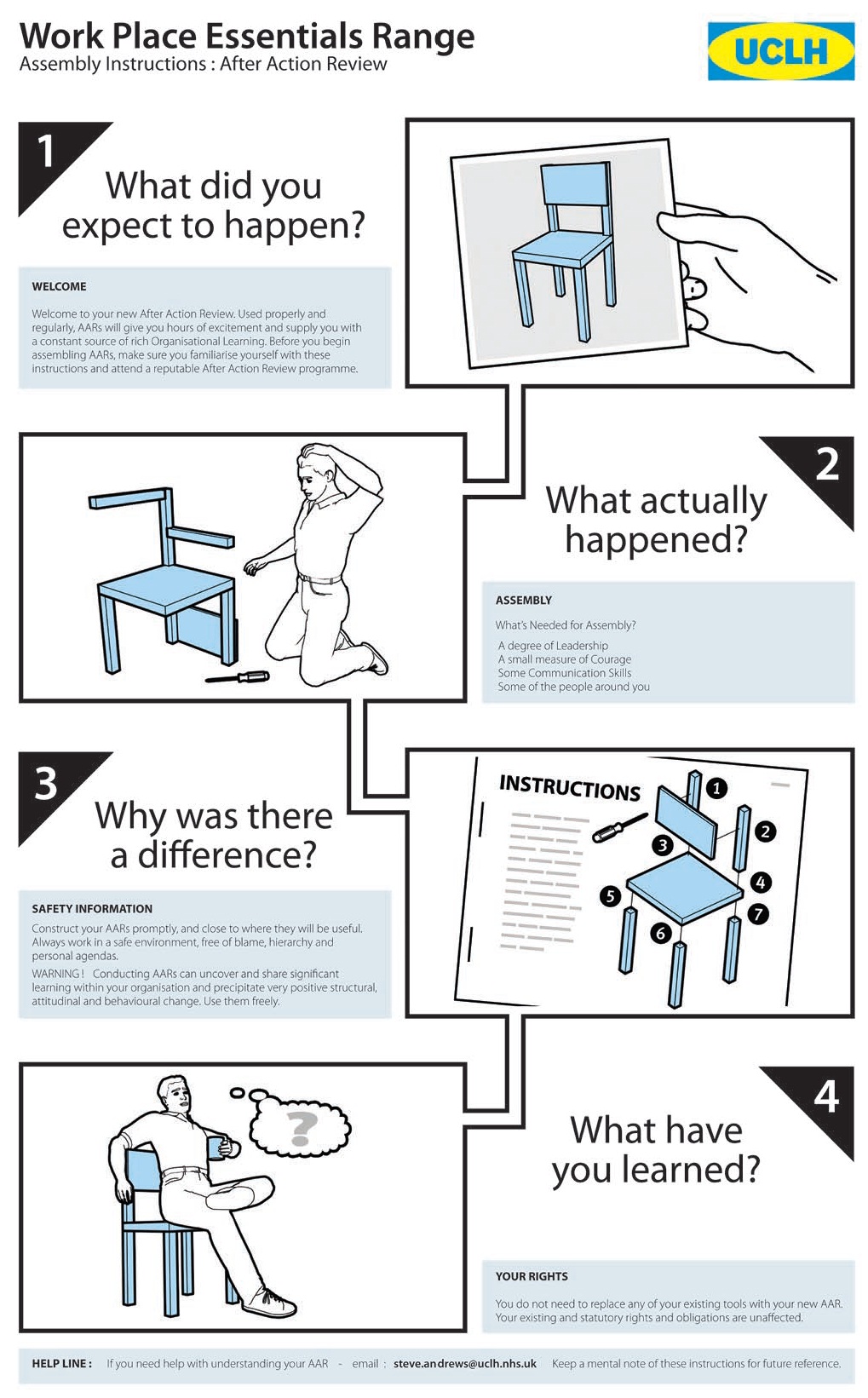

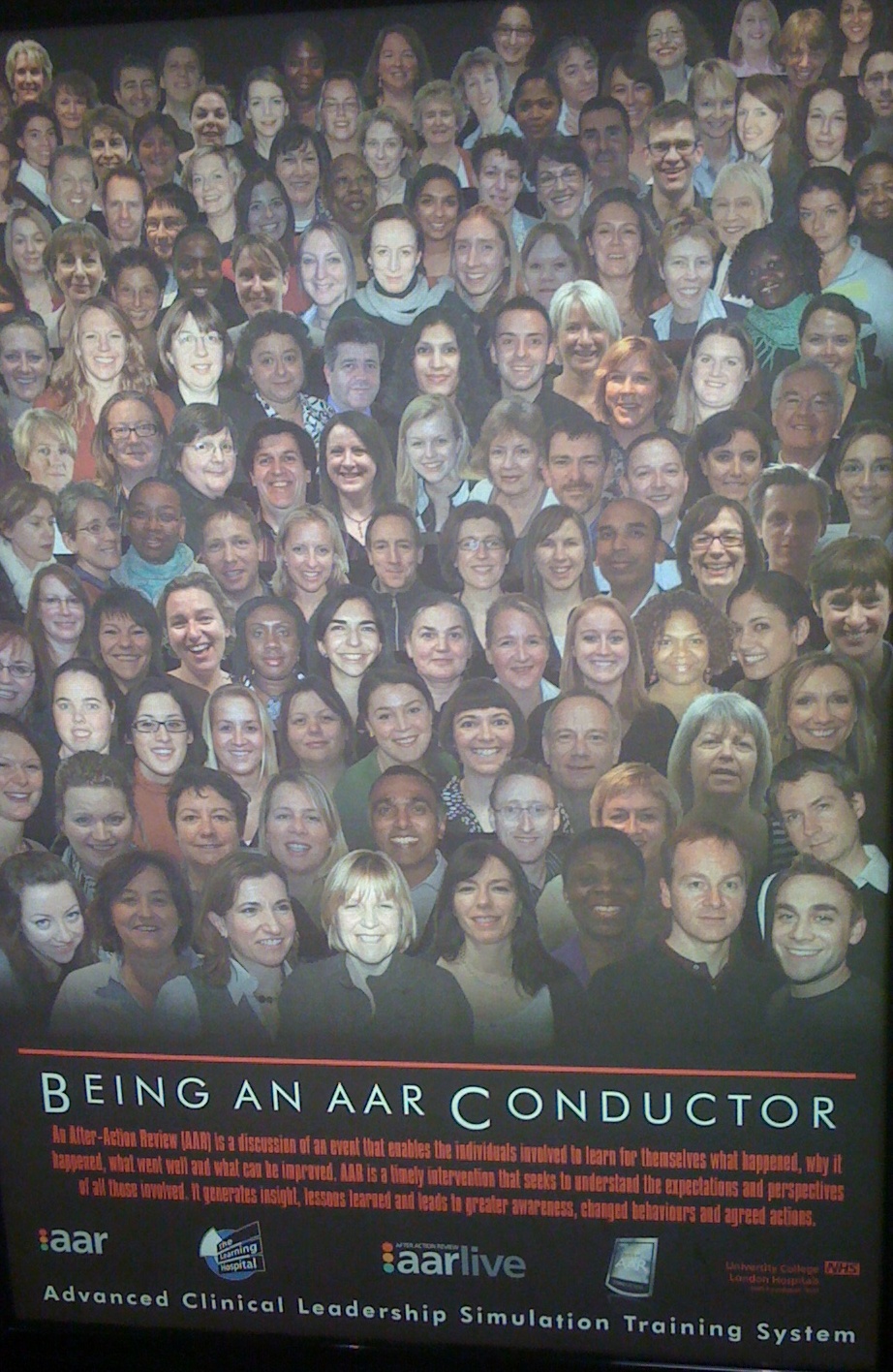

This very real experience is then the basis for staff to conduct after action reviews, to be videoed, review and discuss with their colleagues, together with the Learning Hospital expert staff. So far, 400 staff have become “AAR Conductors”, carrying out reviews in a variety of situations.

This very real experience is then the basis for staff to conduct after action reviews, to be videoed, review and discuss with their colleagues, together with the Learning Hospital expert staff. So far, 400 staff have become “AAR Conductors”, carrying out reviews in a variety of situations.