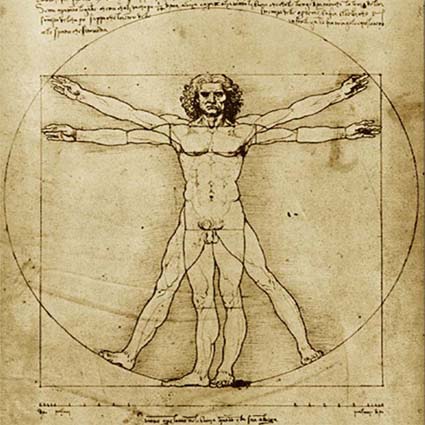

My post on “What did Einstein know about KM” last week seemed to go down well, so I have continued my search for KM musings from great figures. This week, we’ll hear from the Leonardo Da Vinci. It wasn’t until I read Gelb’s ambitiously titled book “How to think like Leonardo do Vinci” that I appreciated just how multi-talented he was. Painter, sculptor, architect, musician, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist, writer and no mean athlete - you name it, he could do it. Curious then that one of his quotations (one of the few which I disagree with) states “As every divided kingdom falls, so every mind divided between many studies confounds and saps itself.“. I guess you can make yourself an exception when you’re the archetypal Renaissance Man Polymath. I wonder what he would have made of the ubiquitous availability of information and possibilities which we enjoy today?

So my curated top-ten quotes from Da Vinci will take us on a journey through different facets of KM: from knowledge acquisition, the way our perceptions filter knowledge, the superiority of expertise over opinions, the power of learning, seeing and making connections, the challenge and value of expressing knowledge simply and the criticality of seeing knowledge applied.

Yes, I would have had him on my KM Team.

- “The knowledge of all things is possible.”

- “The acquisition of knowledge is always of use to the intellect, because it may thus drive out useless things and retain the good.”

- “All our knowledge has its origins in our perceptions.”

- “The greatest deception men suffer is from their own opinions.”

- “Experience is the mother of all Knowledge. Wisdom is the daughter of experience.”

- “Although nature commences with reason and ends in experience it is necessary for us to do the opposite, that is to commence with experience and from this to proceed to investigate the reason.”

- “Learning is the only thing the mind never exhausts, never fears, and never regrets.”

- “Principles for the Development of a Complete Mind: Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses - especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”

- “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.”

- “Knowing is not enough; we must apply.”

I couldn’t find a suitable infographic to illustrate these (I'm sure Leonardo would have produced a very good one if he'd not been so busy), but the book I mentioned earlier insightfully looks at the seven different deliberate practices he drew upon. They’re an excellent set of frames through which to consider our approaches to life and work.

How does your Knowledge Management practice measure up against these?

- Curiosita: Approaching life with insatiable curiosity and an unrelenting quest for continuous learning.

- Dimostrazione: Committing to test knowledge through experience, persistence and a willingness to learn from mistakes.

- Sensazione: Continually refining the senses, especially sight, as the means to enliven experience.

- Sfumato: Embracing ambiguity, paradox and uncertainty.

- Arte/Scienza : Balancing science and art, logic and imagination - ‘whole-brain thinking’.

- Corporalita: Cultivating grace, ambidexterity, fitness, and poise.

- Connessione: Recognizing and appreciating the interconnectedness of all things – ‘systems thinking’.

Leo, you're not just on the team; you can write the KM Strategy!