Back in 2009, I blogged about some heart-warming examples of cross-industry peer assists, involving Great Ormond Street Hospital and the Ferrari Formula 1 pit team. Geoff and I wrote the story up fully in our second book, "No more Consultants". The specific example related to the operating theatre team improving their handover processes during an operation called the "arterial switch" - and the insights of Professor Martin Elliott and his colleagues who had the curiosity and the passion to approach Ferrari and ask for help.

It reminded me of Thomas Friedman's book "The World is Flat" where he wrote:

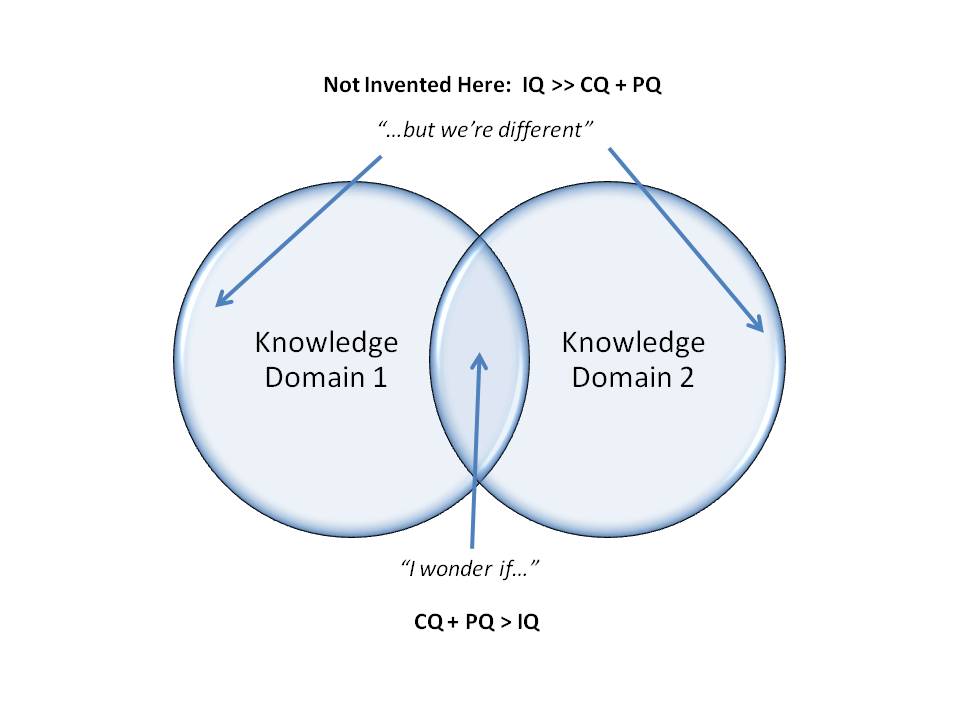

“I have concluded that in a flat world, IQ- Intelligence Quotient – still matters, but CQ and PQ – Curioity Quotient and Passion Quotient – matter even more. I live by the equation CQ+PQ>IQ. Give me a kid with a passion to learn and a curiosity to discover and I will take him or her over a less passionate kid with a high IQ every day of the week.”

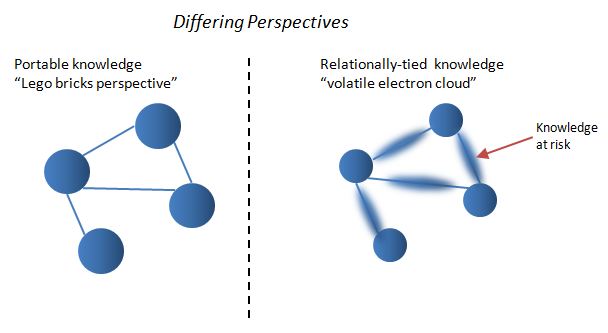

I was interested to see that Formula One was in the news again this week with another example of curiosity-driven cross-sector knowledge sharing - this time with public transport. Train manufacturer Alstom, who say that the knowledge they gained has enabled them reduce a 2-day repair job to just 4 hours.

We need more of these "I wonder" moments to bring knowledge together, where curiosity triumphs over the "but we're different" default reaction of not-invented-here cultures which drives those connections and overlaps apart.